How having cancer becomes about everyone else.

You’ve got cancer.

Three (well, three and a half) little words that echo throughout your brain space, soon followed by silent ‘What The F*’ screams. Nothing else matters. No one else exists at that moment, except the poor doctor facing opposite you, telling you that your life has forever changed.

Cancer should be eligible for a UN peace prize – it doesn’t discriminate. People. Pets. Babies. Mothers. Criminals. Saints.

I just sat there, alone, wondering how I had managed to walk onto the set of someone else's movie.

For whatever reason, today, cancer chose me.

So far, it has become a timely reminder that the strength and resilience (I hate that word by the way) that I thought I had lost years ago was in fact still within, ready and willing to face war. And it does feel like that – a war. But you quickly realise that the battles (most of which are all ahead of you with a big ‘To Be Confirmed’ sign attached) are being fought on many fronts. Family, friends, loves of life, all hear the ‘C’ word and it becomes all about them. It’s about you, yes, but it’s also about their fear of losing you, of not having any say in the matter, of picturing what life might be like without you.

Mothers – the ever-enduring and self-sacrificing “it should have been me.”

Sisters – the silent hugging and sobbing. Followed by just silence.

Fathers – the palpable pain and regret for not being able to protect their daughter.

Life loves – the collision of helplessness and hopefulness etched on a face.

Friends – the tears on standby as they feel the weight of the bomb residue left behind after hearing your "news".

Then there’s the complimentary reminder from the insurance company that you’ve got death coverage, should you need it.

And the remarks from people who are parents that my impending infertility is a blessing because they could quite easily strangle their beloved Little Johnny lately...

And so it comes again. In waves – the pity party for one, followed by the stench of stoicism. Then anger masking complete fear and panic. Then disbelief. An out of body experience. The desperate need to go and lose yourself in a cheap comedic cinematic experience to just forget for two hours that This. Is. Actually. Happening.

I kept hearing the words "you’re a fighter, you’ll beat this, cancer has no idea who it picked a fight with". But I could not, and would not, identify comfortably as a fighter or a survivor. To me, it means I’ve allowed cancer to determine roles and responsibilities from the outset – me: the fighter, and cancer: the aggressor. I was very fortunate to have acted on early warning signs and avoided an all out assault. I chose instead to view my experience as a life preserving mission, not a fight to the death. Literally. Because to me, ‘fighter’ respectfully belongs to all those souls who have been given the worst odds that life could offer, like a woman who dies within 6 weeks of diagnosis because a recurring chest infection was actually stage 4 lung cancer. Or a man with brain cancer who valiantly leaves his life on his own terms because he knew he’d done all he could and it was never going to be enough. They are the ones who have to fight against the knowledge that nothing, short of a miracle, was going to reverse the carnage that cancer had bestowed upon their bodies. Fighting is about finding the courage to keep moving when there is nothing to move towards except death. It is about the strength to claw onto every inch of dignity and independence when all that is left is silent acceptance of the truth that you cannot win this round.

I instead move politely out of the way when someone is using words like fighter or survivor. I’m just someone who copped a crappy body-intruder, who now needed some treatment with crappy side effects. But more importantly, I'm someone who is gripping tightly to a reason to make a lifelong pledge to myself and my beloveds to truly live and honour the value of life and also hope that this MOFO never finds reason to come back for a follow up visit.

Breast cancer is a funny one – we all grow up feeling self-conscious as young girls, especially ones like me who ‘developed early’. I had boys flicking my bra strap in year 6 that left me begging, pleading my mum to only make me wear the bra at night time so that I would stop being picked on and laughed at. Clueless of course that the law of gravity was not on my side! But this marked the start of a long journey into womanhood rejecting the reflection in the mirror. I was too tall, too pale, too heavy, too nerdy, too ambitious, too stubborn, too independent, too much to warrant the acceptance of myself. How ironic that it was the reflection in the mirror years later that would now save my life.

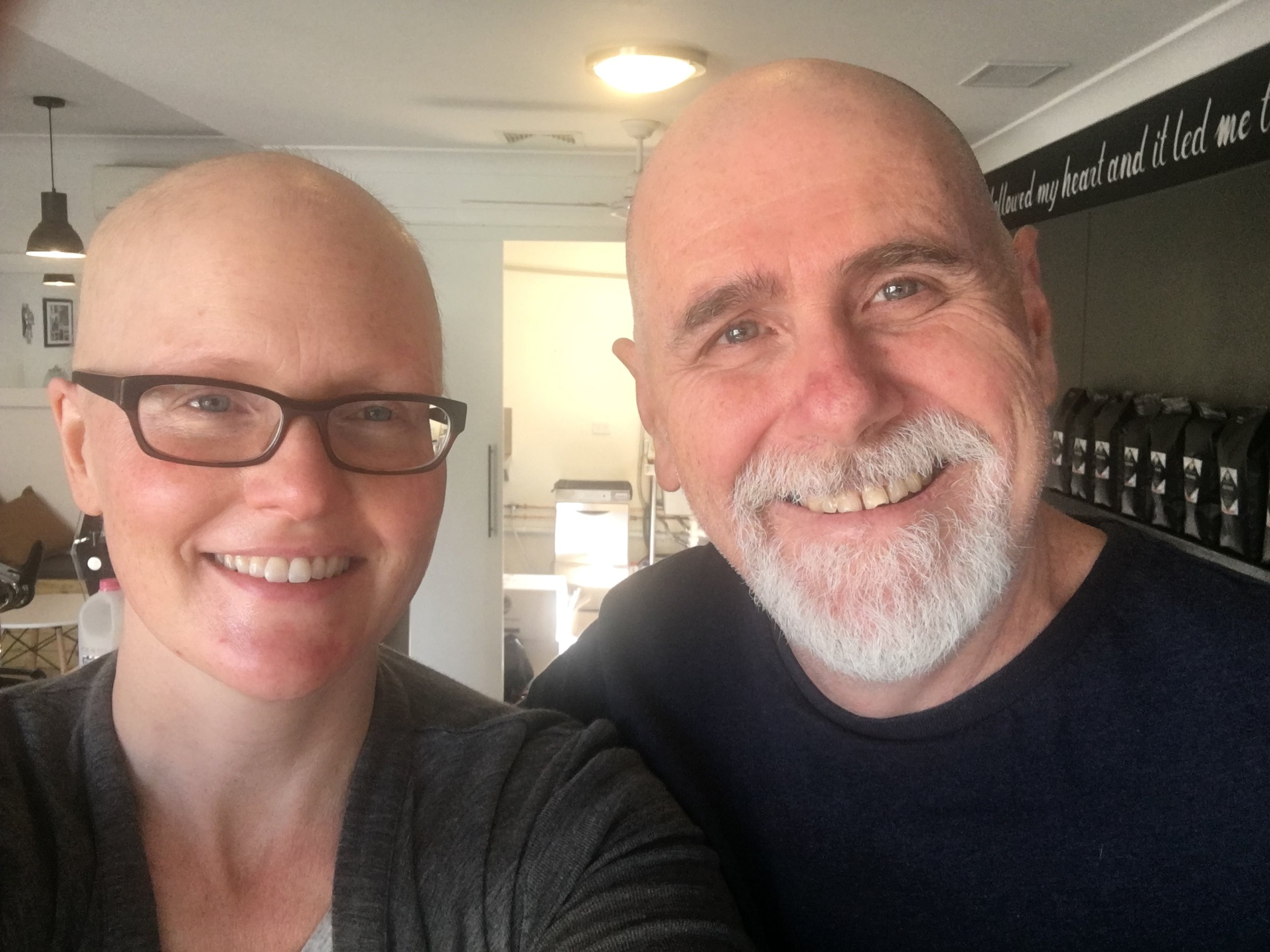

In the absence of an apparently never-ending list of 'I love me nots', I focused on my two greatest assets: my hair and my ‘epic cannons’ (aptly described once…). They became critical to defining my self-worth but had never really extended to self-love. A dear friend once said to me that one day, I would meet a guy who saw me for more than just a pair of boobs and long hair. And she was right. But cancer has re-planted that resounding fear in my head about how I embrace who I am as a woman if I didn't have my long hair, or boobs, or uterus, or ovaries, or having birthed a child.

In the meantime, I am replacing the list of baseless fears with an Indiana Jones-style re-make with me front and centre in the search for my own holy grail. I found out that in eastern medicine the heart meridian line runs from my left hand up my arm, through my left breast and under my arm/shoulder. Bingo. That gap in self-love is exactly where cancer has taken up residence. So, in part it’s understanding my gene pool, but more importantly it’s about treating myself with care and kindness and understanding and acceptance - all the things I have offered to others but rarely myself.

The first step is making this all about ME in the ultimate act of honour and self-preservation. No one else can do that, no matter how hard they want to. Part of that is learning how to give love back to whatever the mirror offers me, especially the days when I don't even recognise the reflection.